Simone Weil’s needs of the soul:

- ORDER

- LIBERTY

- OBEDIENCE

- RESPONSIBILITY

- EQUALITY

- HIERARCHISM

- HONOUR

- PUNISHMENT

- FREEDOM OF OPINION

- SECURITY

- RISK

- PRIVATE PROPERTY

- COLLECTIVE PROPERTY

- TRUTH

- ROOTS

Reading and writing about education I have come to ideas about freedom – those of Simone Weil who describes freedom as the link between thought and action can be seen as a common thread in texts about education. By texts about Impersonalism and Zen Buddhism I have come to questions about the nature of thought – how thought comes to us and how skillfully interacting with it is a prerequisite for a practice of freedom.

I would like to reassess the question of the purpose of education and it’s intrinsic relationship to freedom, and to reveal the impersonal intertwined with it – that which is not of the self.

To talk about freedom I first have to talk about Simone Weil’s ideas about collectivity. Although today we develop into collectivity in ways unfathomable to past societies; in a lot of ways we dabble in socialization online before we have the physical experiences that solidify its role in our participation in the world by a practice of socializing, Weil’s observations about collectivity, despite being drawn from a collectivity of a different form, apply in the same ways. Our biological and social need for collectivity can be understood, Weil explains, as analogous to the need for food.

The fact that a human being possesses an eternal destiny imposes only one obligation: respect. The obligation is only performed if the respect is effectively expressed in a real, not a fictitious, way; and this can only be done through the medium of Man’s earthly needs.1

We owe a cornfield respect, not because of itself, but because it is food for mankind.2

Simone Weil

Obligation is shown to be sacred; upon its fulfilment it is sustenance. Using ‘Man’s earthly needs’ as a medium for fulfilling obligation uncovers an understandable value and need for collectivity, however, collectivity is not pure good, it is separate from good – it levels below it, that is, it is subordinate to good.

There are collectivities which, instead of serving as food, do just the opposite: they devour souls . . .3

What frightens me is the Church as a social structure. Not only on account of its blemishes, but from the very fact that it is something social. It is not that I am of a very individualistic temperament. I am afraid for the opposite reason. I am aware of very strong gregarious tendencies in myself. My natural disposition is to be very easily influenced, too much influenced – and above all by anything collective. I know that if at this moment I had before me a group of twenty young Germans singing Nazi songs in chorus, a part of my soul would instantly become Nazi. That is a very great weakness, but that is how I am. I think that it is useless to fight directly against natural weaknesses. One has to force oneself to act as though one did not have them in circumstances where duty makes it imperative; and in the ordinary course of life one has to know these weaknesses, prudently take them into account, and strive to turn them to good purpose.4

Simone Weil

When collectivity acts as though a person is subordinate to it; giving it the characteristics of self in the place of a real relationship with self by way of idolatry, there is injustice. A collective must not primarily or essentially influence oneself. We must learn about collectivity as subordinate to methods of knowledge and methods of knowledge as subordinate to self and that there is an essential non-conceptual immediacy prior to self.5

Simone Weil explains that we can move from ‘we’ to ‘I’ and from ‘I’ to the impersonal but we cannot move from ‘we’ to the impersonal.

Simone Weil

The collectivity is not only alien to the sacred, but it deludes us with a false imitation of it.6

A collectivity is much stronger than a single man; but every collectivity depends for its existence upon operations, of which simple addition is the elementary example, which can only be performed by a mind in a state of solitude. This dependence suggests a method of giving the impersonal a hold on the collective, if only we could find out how to use it.7

Simone Weil

As a product of the needs of the soul collectivity is clear; it is intertwined with obligation. Speaking of obligations Weil says:

No human being, whoever he may be, under whatever circumstances, can escape them without being guilty of crime; save where there are two genuine obligations which are in fact incompatible, and a man is forced to sacrifice one of them. The imperfections of a social order can be measured by the number of situations of this kind it harbors within itself . . . There exists an obligation towards every human being, without any other condition requiring to be fulfilled, and even without any recognitions of such obligation on the part of the individual concerned.8

Simone Weil

We must strive to have goodness inform the order of collectivity by way of the ability to meet the obligations owed to every human being – so that these obligations are compatible with one another. To strive to fulfil these obligations and succeed is to align with the needs of the soul that facilitate freedom. This freedom equates to a sacrifice of self which requires a relationship with self in order to practice freedom. We can sacrifice without all of these needs being met and we do but this is an injustice and we must strive for better.

This sacrifice can be understood as the process of moving from ‘I’ to the impersonal – it is action of an impersonal nature.

The human being can only escape from the collective by raising himself above the personal and entering into the impersonal. The moment he does this, there is something in him, a small portion of his soul, upon which nothing of the collective can get a hold. If he can root himself in the impersonal good so as to be able to draw energy from it, then he is in a condition, whenever he feels the obligation to do so, to bring to bear without any outside help, against any collectivity, a small but real force.9

Simone Weil

Essential human obligations are directly linked to goodness that is the essence of all human action including education – and the respect for all things good that these obligations equate to is the purpose; it is the work that strives for goodness.

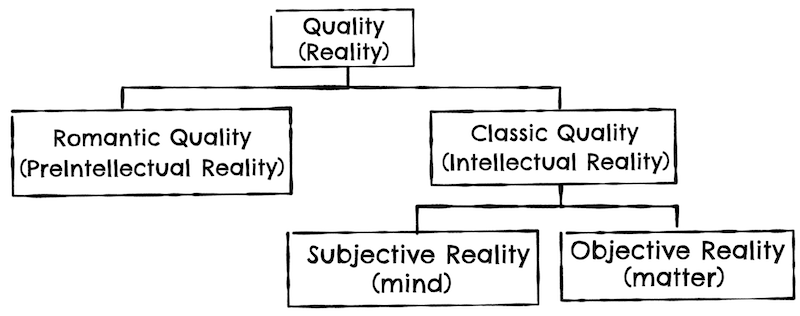

This essence is a visceral understanding of better – described by Simone as goodness and truth, by Zen Buddhism and Christianity as good and by Pirsig as Quality and value. For these philosophies goodness is understood as inherent in a person, felt by them. In each one, there is a guide – for Simone and Pirsig it is beauty, for Zen Buddhism it is the Tathagata and in Christianity it is the Holy Spirit.

The fulfilment of the needs of the soul

Sacrifice is at the heart of true action. It is the experience of moving through the world with full attention; simply and with clarity.

True action; not that which emanates from the passions, from the unbridled imagination but action that conforms to geometry, that is to say which is brought into being through knowledge of the world that is gained by moving progressively from one simple idea to another.10

Simone Weil

Sacrifice allows true communion with action and this means true communion with the world. To work to the end of goodness with attention and without self is to sacrifice.

Physical labor is a daily death. To labor is to place one’s own being, body and soul, in the circuit of inert matter, turn it into an intermediary between one state and another of a fragment of matter, to make of it an instrument. The laborer turns his body and soul into an appendix of the tool which he handles. The movements of the body and the concentration of the mind are a function of the requirements of the tool, which itself is adapted to the matter being worked upon. Death and labor are things of necessity and not choice. The world only gives itself to man in the form of food and warmth if man gives himself to the world in the form of labor. But death and labor can be submitted to either in an attitude of revolt or in one of consent. They can be submitted to either in their naked truth or else wrapped around with lies11.

Simone Weil

Our relationship with the self has been desecrated and work no longer aligns with the needs of the soul. The purpose of education is sacred and must be transformed to reflect this.

Subhuti, if there be a good man or a good woman who gives away his or her lives as many as the sands of Ganga, his or her merit thus gained does not exceed that of one who, holding even one gatha of four lines from this sutra, preaches them for others.12

Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki

- Weil, S. (2021). Need For Roots. S.L.: Penguin Books. P.6 ↩︎

- Weil, S. (2021). Need For Roots. S.L.: Penguin Books. ↩︎

- Weil, S. and Miles, S. (2005). Simone Weil : an anthology. London: Penguin. ↩︎

- Weil, S. and Miles, S. (2005). Simone Weil : an anthology. London: Penguin. P.4 ↩︎

- Pirsig, R.M. (2014). Zen and the art of motorcycle maintenance : an inquiry into values.

↩︎

↩︎ - Weil, S. and Miles, S. (2005). Simone Weil : an anthology. London: Penguin. ↩︎

- Weil, S. and Miles, S. (2005). Simone Weil : an anthology. London: Penguin. ↩︎

- Weil, S. and Miles, S. (2005). Simone Weil : an anthology. London: Penguin. P.107 ↩︎

- Weil, S. and Miles, S. (2005). Simone Weil : an anthology. London: Penguin. ↩︎

- Weil, S. and Miles, S. (2005). Simone Weil : an anthology. London: Penguin. ↩︎

- Weil, S. and Miles, S. (2005). Simone Weil : an anthology. London: Penguin. P.61 ↩︎

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki (2019). Manual Of Zen Buddhism. S.L.: Bibliotech Press. P.45 ↩︎

Leave a comment